Section 1.4 Instant Insanity

So far, our motivation for studying graph theory has largely been one of philosophy and language. Before we get too much deeper, however, it may be useful to present a nontrivial and perhaps unexpected application of graph theory; an example where graph theory helps us to do something that would be difficult or impossible to do without it.

Subsection 1.4.1 A puzzle

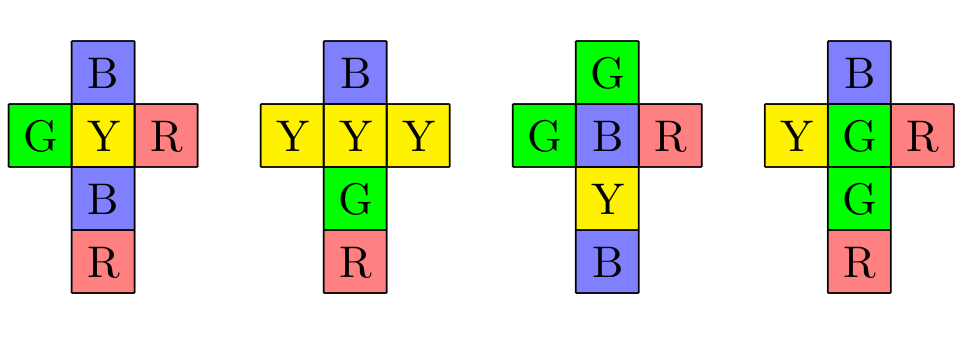

There is a puazzle marketed under the name "Instant Insanity", one version of which is shown above. The puzzle is sometimes called "the four cubes problem", as it consists of four different cubes. Each face of each cube is painted one of four different colours: blue, green, red or yellow. The goal of the puzzle is to line the four cubes up in a row, so that along the four long edges (front, top, back, bottom) each of the four colours appears eactly once.

Depending on how the cubes are coloured, this may be not be possible, or there may be many such possibilities. In the original instant insanity, there is exactly one solution (up to certain equivalences of cube positions). The point of the cubes is that there are a large number of possible cube configurations, and so if you just look for a solution without being extremely systematic, it is highly unlikely you will find it.

But trying to be systematic and logical about the search directly is quite difficult, perhaps because we have problems holding the picture of the cube in our mind. In what follows, we will introduce a way to translate the instant insanity puzzle into a question in graph theory. This is obviously in no way necessary to solve the puzzle, but does make it much easier. It also demonstrates the real power of graph theory as a visualization and thought aid.

There are many variations on Instant Insanity, discussions of which can be found here and here. There’s also a commercial for the game.

Subsection 1.4.2 Enter graph theory

It turns out that the important factor of the cubes is what color is on the opposite side of each face. Suppose we want face one facing forward. Then we have four different ways to rotate the cube to keep this the same. The same face will always appear on the opposite side, but we can get any of the remaining four faces to be on top, say.

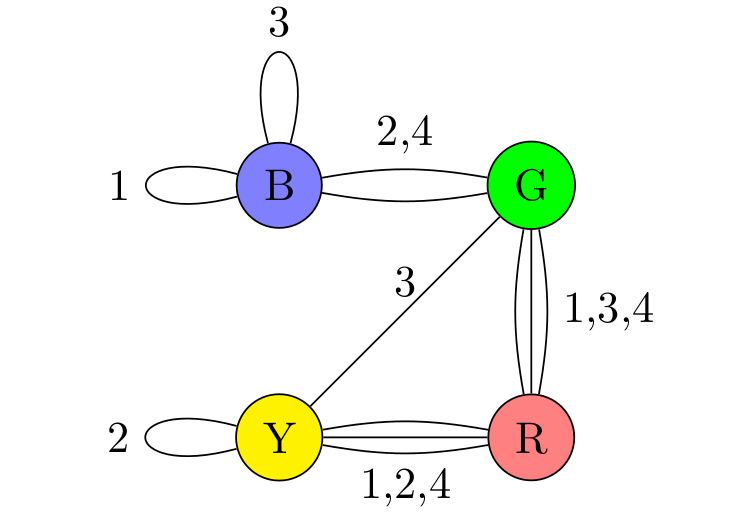

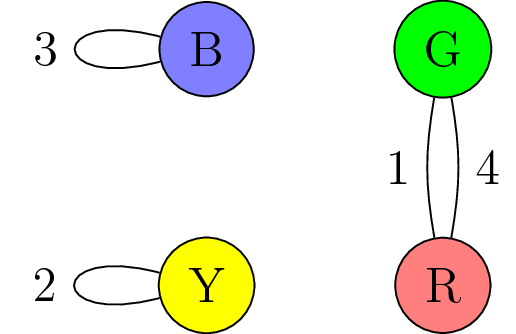

Let us encode this information in a graph. The vertices of the graph will be the four colors, B, G, R and Y. We will put an edge between two colors each time they appear as opposite faces on a cube, and we will label that edge with a number 1-4 denoting which cube the two opposite faces appear. Thus, in the end the graph will have twelve edges, three with each label 1-4. For from the first cube, there will be a loop at B, and edge between G and R, and an edge between Y and R. The graph corresponding to the four cubes above is the following:

Subsection 1.4.3 Proving that our cubes were impossible

We now analyze the graph to prove that this set of cubes is not possible.

Suppose we had an arrangement of the cubes that was a solution. Then, from each cube, pick the edge representing the colors facing front and back on that cube. These four edges are a subgraph of our original graph, with one edge of each label, since we picked one edge from each cube. Furthermore, since we assumed the arrangement of cubes was a solution of instant insanity, each color appears once on the front face and once on the back. In terms of our subgraph, this translates into asking that each vertex has degree two.

We can get another subgraph satisfying these two properties by looking at the faces on the top and bottom for each cube and taking the corresponding edges. Furthermore, these two subgraphs do not have any edges in common.

Thus, given a solution to the instant insanity problem, we found a pair of subgraphs \(S_1, S_2\) satisfying:

- Each subgraph \(S_i\) has one edge with each label 1,2,3,4

- Every vertex of \(S_i\) has degree 2

- No edge of the original graph is used in both \(S_1\) and \(S_2\)

As an exercise, one can check that given a pair of subgraphs satisfying 1-3, one can produce a solution to the instant insanity puzzle.

Thus, to show the set of cubes we are currently examining does not have a solution, we need to show that the graph does not have two subgraphs satisfying properties 1-3.

To do, this, we catalog all graphs satisfying properties 1-2. If every vertex has degree 2, either:

- Every vertex has a loop

- There is one vertex with a loop, and the rest are in a triangle

- There are two vertices with loops and a double edge between the other two vertices

- There are two pairs of double edges

- All the vertices live in one four cycle

- A subgraphs of type 1 is not possible, because G and R do not have loops.

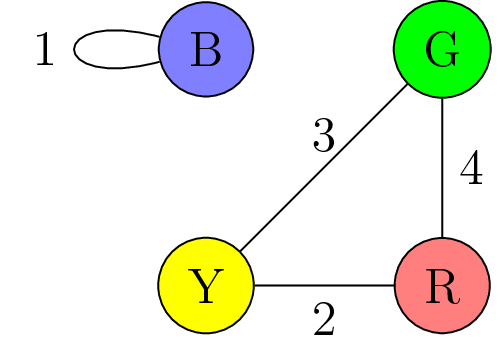

For subgraphs of type 2, the only triangle is G-R-Y, and B does have loops. The edge between Y-G must be labeled 3, which means the loop at B must be labeled 1. This means the edge between G and R must be labeled 4 and the edge between Y and R must be 2, giving the following subgraph:

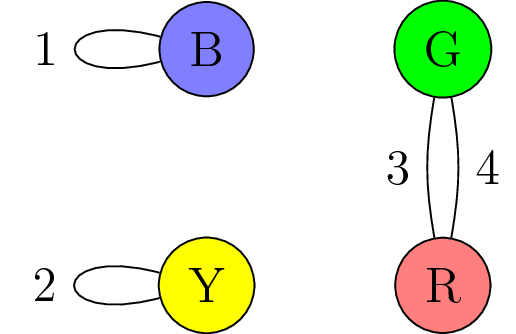

For type 3, the only option is to have loops at B and Y and a double edge between G and R. We see the loop at Y must be labeled 2, one of the edges between G and R must be 4, and the loop at B and the other edge between G and R can switch between 1 and 3, giving two possibilities:

For subgraphs of type 4, the only option would be to have a double edge between B and G and another between Y and R; however, none of these edges are labeled 3 and this option is not possible.

Finally, subgraphs of type 5 cannot happen because B is only adjacent to G and to itself; to be in a four cycle it would have two be adjacent to two vertices that aren’t itself.

This gives three different possibilities for the subgraphs SiSi that satisfy properties 1 and 2. However, all three possibilities contain the the edge labeled 4 between G and R; hence we cannot choice two of them with disjoint edges, and the instant insanity puzzle with these cubes does not have a solution.

Subsection 1.4.4 Other cube sets

The methods above also give a way to find the solution to a set of instant insanity cubes should one exist. I illustrate this in the following Youtube video: